Unintentional Prison: A Humane Approach to Rehabilitation Architecture

A humane correctional prototype redefining rehabilitation architecture for non-violent cyber offenders in the digital age.

Project by Mohammad Farooqui

Shortlisted entry of Switching Prisons

Juror Comments:"Architecturally well resolved - not like a prison at all. Well done." – Michael Spight, Director, TAG Architects, Australia"Interesting working environment." – Misak Terzibasiyan, Founder and CEO, UArchitects, Netherlands

In the evolving realm of rehabilitation architecture, a new paradigm is being explored—one that recognizes the complexity of cyber and non-physical crimes, and more importantly, the psychological and social context of those who commit them. "Unintentional Prison" by Mohammad Farooqui presents a radical departure from traditional penitentiary design, rethinking confinement not as a fortress but as an environment of structured freedom, self-awareness, and social reintegration.

The project challenges a core assumption: that absolute security equals complete isolation. Historical precedent shows that even maximum-security prisons are fallible. But what if the real focus shifted from containment to correction? Farooqui's proposal addresses individuals who have committed non-violent, cyber-based, or unintentional offenses, many of whom are neither dangerous nor chronically criminal. They might be youth, first-time offenders, or people misled into digital infractions.

An Operating System Analogy The design metaphor draws on digital systems, likening the prison to a broken operating system. Instead of treating inmates as malicious data to be erased, the architecture acts as a firewall and recovery tool—repairing, reconnecting, and re-securing both individual behavior and societal norms. The built environment thus becomes a living interface of behavioral recovery.

A Micro-City of Care and Responsibility Rather than conventional cells and isolating corridors, the "Unintentional Prison" recreates a full urban ecosystem within its secure boundaries. Roads, retail shops, cafés, co-working hubs, banks, auditoriums, and wellness zones are all part of this semi-open environment. Prisoners live in residential towers—seven of them—linked to a podium base that supports core social programs.

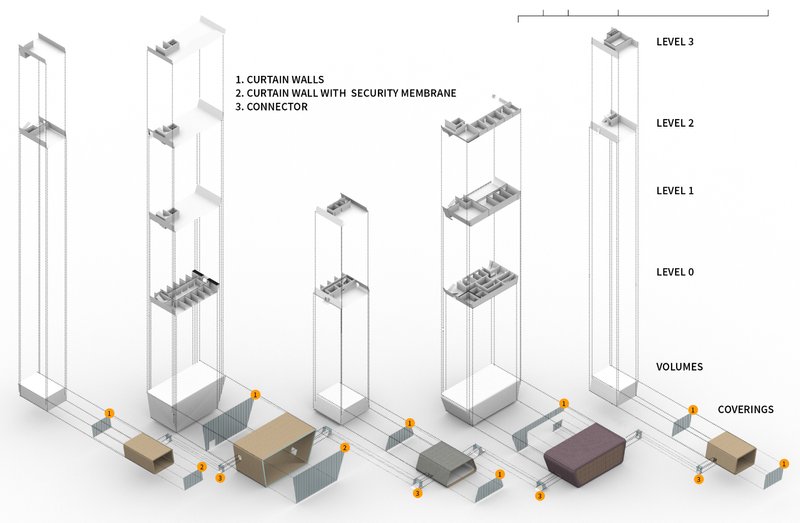

Each building layer serves a function beyond containment:

- Level 0: Reception, visitor meeting areas, retail shops, interrogation and temporary holding rooms.

- Level 1 & 2: Administrative offices, co-working areas, training rooms, and system monitoring.

- Level 3: Libraries, control centers, dining and multi-functional public areas.

Prisoners and officers share co-working spaces—a symbolic and practical gesture of trust-building. Inmates participate in training, digital literacy, cybersecurity, and tech industry-aligned work, bridging their sentence with future employability.

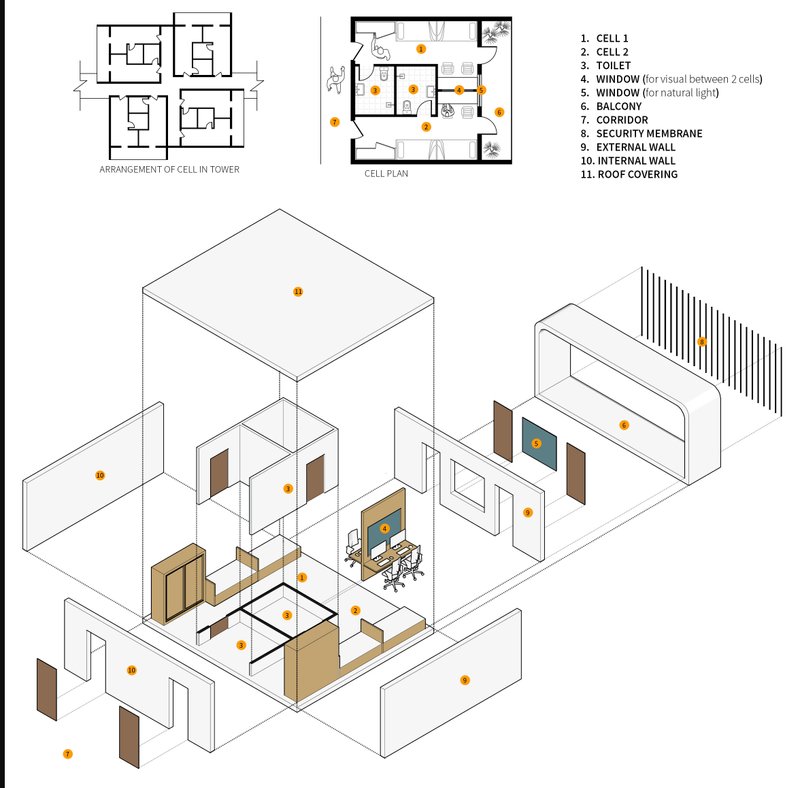

Spatial Freedom, Psychological Respect Cells are designed not as cages but as minimal apartments. Each unit contains two separate rooms, a shared bathroom, balconies, and windows—both for daylight and transparency. Visual communication between adjacent cells is encouraged, reducing psychological fatigue.

The walls and structure utilize layered security membranes rather than brute fortification. The outer boundary is a web-secured zone—conceptually and technologically reinforcing the architecture’s digital metaphor.

Architecture as a Tool for Redemption This is not about leniency, but about logic. Why isolate those who are already detached from physical violence? Farooqui’s vision sees design not as punishment but as programming: a structured yet open system of reformation.

The "Unintentional Prison" is less about the walls that confine, and more about the architecture that liberates—from stigma, recidivism, and neglect. It exemplifies the core potential of rehabilitation architecture in an era where crime and identity are increasingly virtual.