The Forest and the City

Tracing the relationship between nature, civilization and architecture through biomimetic architecture

Since the start of mankind, industry has significantly progressed during the last 100 years. If you were to compare the progress of industrialization in modern times with that of all human history up till this point, it would occur in less than a minute, 1 within 1% of our total time as humans on Earth. To put this into perspective, during the 10 centuries before 1900, humankind experienced an average rate of industrialization that was only 1/10th what we see today. Although the rapid rate of industrialization has helped to alleviate suffering thanks to new technological conveniences and medical innovations, it has also increased pollution and has created environmental destruction. In this drift towards industrialization men have continually striven to create more products that can be an improvement upon one's life.

However, mankind faces a limited amount of resources to live on. We may not always have found a clear solution to the problem of living within natures constrains, but we can learn from the answer that is always within nature. It has even been suggested that studying nature could help with problems related to the lack of resources or survival issues at hand. Biomimetic is therefore, an area which uses nature as a model to solve these problems and it has recently seen increased growth in interest from mankind. This review takes a closer look at just some examples of biomimetic, including how they are being applied today as well as what the potential future holds for them in terms of use going forward.

Biomimicry (bios — life and mimesis — imitate) refers to the act of innovating by taking inspiration from nature and its designs. Nature has taught us how to survive in a constantly changing environment. We call this phenomenon evolution, and it can all be explained by the principle of mutation, recombination, and selection.

Nature is terrific at turning waste into food—a fundamental tool for balancing ecosystems that architecture has, for the most part, ignored throughout history. But to many designers, learning how to use biology as a model for resource stewardship and circular economies is vital to designing structures under the constraints faced by nature. Biology also practices a kind of “critical regionalism” in which architects learn about their locations first hand and then design buildings suited to the geography and culture of their setting. For example, there are parasites that are only able to live in one specific host species, meaning they are specially evolved to survive with particular organisms exclusively.

What is biomimetic architecture? When did it all start?

Biomimetic architecture is based on the idea that nature's inhabitants - including animals, plants and microbes - have survived more successfully than humans using their own adaptability to change with the environment in order to exist. Biomimetic architecture looks to nature for answers on how to create sustainable buildings using natural forms and learning from principles found within them.

An architect and engineer, Filippo Brunelleschi is considered to be the father of working of living structures. Long before he took over projects like the Florence Cathedral dome, he frequented botanical gardens, where he learned that studying structural design wasn’t just about looking at something but also observing its behaviour against forces beyond gravity. It was this knowledge that inspired him to design a thinner, lighter dome for his new cathedral in Florence.

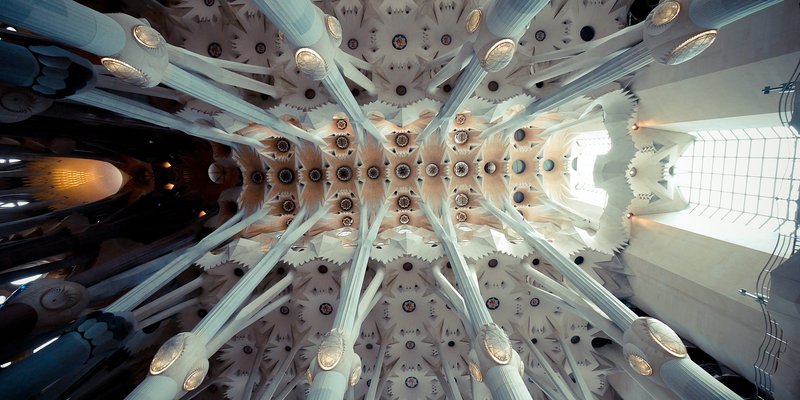

The Sagrada Famila designed by Antonio Gaudi is heavily inspired by the forest canopy.

Green innovations leading the 'Biomimetic Revolution'.

The innovators of biomimicry came to this design movement not by looking for ways that nature could solve engineering problems, but by discovering that the most efficient solutions often consisted of materials mimicking natural objects. Nature, "uses very little material and places it in the right place," they say. It's effective because it is derivative of artistic expressions. The folk artists used what they could find and make their art out of a combination of sticks, stones, straws and many other ordinary objects from their daily lives. All this in order to be able to have an impact on society through art.

Facade design

MIMOCAP, the studio of Belgian architect Luca Adriaenssens, has created a series of proposals for self-adapting facades that respond to sunlight by swelling and shrinking like monocellular organisms. These detailed studies in biomimicry answer a call made last year by Geoffrey B. West, President of the Santa Fe Institute, an interdisciplinary centre where physicists and urban designers collaborate on scientific research.

In a lecture entitled “Architecture + Biology = Molecular Technology”, West looked at major advances in building control systems and speculated that there might be equally large innovations yet to come from architects if only they were willing to abandon their obsession with aesthetics—which he described as essentially narcissistic—and instead learn from nature: “The single obsession that comes before everything else is survival and flourishing; it seems clear we can get enormously far just by copying some aspects of what happens in biology".

Material Invention

Biomimicry is a new field with loosely defined borders, but broadly speaking, there are two approaches: simulation of biological processes and the co-option of living material, called bio-utilization. Aiming to reduce carbon emissions in brick manufacturing, bioMASON grows brick kiln-free in its North Carolina greenhouse. "What we're creating is biological cement," says founder and CEO Ginger Krieg Dosier. We developed a process that uses bacteria to alter the pH balance of the surrounding aggregate material so calcium carbonate can grow and bind the material together, resulting in little to no carbon emissions. This is something similar to what happens in nature when using coral reefs as an example. Calcium and carbon dioxide combine with help from mineral ions, such as magnesium or potassium, to form calcium carbonate and other compounds called calcium-carbonate-binders. These bricks are almost on par with regular bricks in terms of cost, but they're much better for our environment.

Building materials like brick contribute to about 12% of all carbon emissions each year. Architects can combat the climate crisis by working with nature rather than the other way around, and one way we can do this is by tapping into the power of biomimicry and biophilic design for sustainable architecture. “The larger vision is getting us to zero-carbon, healthy, and vibrant buildings for all” says Director of Sustainability Eric Corey Freed. “Mainstreaming biomimicry – i.e. the design process that allows us to learn from nature - and biophilic design – i.e. the integration of nature into design processes - helps achieve this goal by refining our understanding of how the natural world operates in order to find innovative solutions for sustainable innovation.”

In conclusion

As with many great things, biomimetics began as a simple imitation of nature. It has taken us to a point where we can use natural structures and elements to create new materials, new systems, and even design innovative ways of production. Through biomimetics, we've moved beyond imitation and are now able to fully understand and use the properties of nature itself! One day, we will have the chance to alter our own present for the better.

We will soon use biomimetics in our work which is a scientifically proven system that uses nature as a model when it comes down to creating new things. By building technology like this and making it part of our economy, we hope to create a more stable and productive future where products are more biodegradable, less harmful for the environment and better for us.