SPATIAL FICTION AND THE GAZING EYE: A NEW READING AT THE INTERSECTION OF CINEMA AND ARCHITECTURE

Through 'The Gazing Eye,' this essay redefines space as an active subject, arguing the architect is now a director of atmosphere.

THE EXISTENTIAL DIALOGUE OF TWO DISCIPLINES

From a superficial perspective, architecture and cinema might be perceived as two disciplines with entirely distinct means of production. One strives to construct a static and permanent reality that defies gravity by stacking stone, concrete, and steel. The other transforms space into a fluid, ephemeral, yet emotionally shattering experience by bending light, sound, and time. However, as Juhani Pallasmaa frequently points out in his architectural theories, the ultimate goal of both arts is surprisingly common: to create "lived spaces" for human beings (Pallasmaa, 2011).

The architect is, in fact, a secret screenwriter who choreographs the daily life of users, directing human movement through voids and masses. The director, on the other hand, is an architect who constructs the emotions of characters through the spaces they inhabit, building walls with camera frames. Therefore, reading this relationship today merely as a technical "history of set design" would be insufficient. The focal point should be how the "gazing eye"—which transforms alongside evolving technology—and the meaning we attribute to space dissolve the boundaries between these two disciplines.

FROM DECOR TO HYBRID REALITY: THE EVOLUTION OF PERCEPTION AND TECHNOLOGY

Looking panoramically at the history of cinema, the representation of space cannot be explained solely by the development of camera technology; it is also an adventure of human spatial perception . In early cinema, particularly in examples of German Expressionism, sets did not concern themselves with imitating physical reality. On the contrary, the slanted walls, distorted perspectives, and exaggerated shadows seen in films like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari were psychological tools that thrust the chaos of the character's inner world and post-war societal traumas into our faces. In that era, space was a theatrical shell that directly encoded emotion.

Over time, the evolution of technology—from giant studio models to the Metropolis era, and from there to today's CGI (Computer Generated Imagery) and Virtual Production technologies—granted directors immense "freedom to design space". However, more critical than the visual quality of technology here is how aesthetic choices hijack the narrative. For instance, The Grand Budapest Hotel demonstrates that architecture and set design are not merely backgrounds, but holistic reflections of the director's visual language, the repetition in symmetry, and a unique color palette.

Today, with films like Inception, the situation has moved to an entirely different dimension. Cinema no longer just shows what exists; it consciously dismantles the rules of the physical world (gravity, perspective, continuity). What is presented to the audience is a hybrid reality where urban textures are montaged, 'known cities' are transformed into mental labyrinths, and non-Euclidean spaces emerge. At this point, cinema stretches the rigid rules of architecture, forcing it to ask the question: "How could it have been?".

Although architecture and cinema have their own disciplinary boundaries and different tools of production, they meet around the same essence: how space is experienced over time and how this experience gains meaning through the "gazing eye". In this context, space is neither merely a physical product of architecture nor a visual background of cinema; on the contrary, it is a multi-layered field of experience established together with time, motion, and perception. In both cases, space ceases to be a static object and becomes a narrative tool that generates new meanings.

THE PROTAGONIST OF THE NARRATIVE: ARCHITECTURAL MOVEMENTS AND COLLECTIVE MEMORY

Interestingly, architectural movements and approaches in films can cease to be mere calendar pages reflecting an era or decorative backdrops; they transform into decisive and guiding elements of the story, actors stealing the leading role. Architectural forms concretize abstract concepts such as status, power, bureaucracy, or ideology, and cinema takes this burden and visualizes it. In cinema, space transcends the physical limits of architecture to become an experiential tool through which ideology, society, memory, and psychology can be read.

This is observable in dystopian films. The raw concrete surfaces and massive scales of Brutalism and Modernism are often used as the spatial counterparts of authoritarian regimes and systems that oppress the individual. The suffocating structures reaching for the sky in A Clockwork Orange or Blade Runner, disconnected from the human scale, are not just urban landscapes; they are pictures of the individual's helplessness, crushed between the gears of the system.

A similar, and perhaps more contemporary, example can be found in Parasite. The architectural section, stairs, and layers of the house in the film constitute the backbone of the story. Wealth and poverty, light and darkness are narrated through the "house above" and the "semi-basement". Here, architecture is the screenplay's strongest actor, narrating class differences through a vertical hierarchy. Even in Jacques Tati's Playtime, the glass walls, transparency, and uniformity brought by Modernism are critiqued with subtle humor through the lens of modern human disconnection. Cinema, by holding a mirror to the sometimes "inhumane" cold face of architecture, pushes architects to question the social impacts of their own designs.

TRANSFER OF METHODS AND POSSIBILITIES

The influence of cinema on architecture is much deeper and more methodological than is assumed. This relationship is not limited to producing "beautiful visuals"; it infiltrates the kitchen of design. Le Corbusier's famous concept of "Promenade Architecturale," which he introduced to modern architecture, is grounded in cinematography. The sequential images perceived while walking through a building, light transitions, and perspective changes are choreographed just like a film strip. When an architect plans how a user will discover the structure step by step and where they will look at which point, they are essentially writing a script and placing space onto a timeline. Architecture frames the journey of everyday life.

Furthermore, cinema functions as a "laboratory of possibilities" for architects. Futuristic cities that are impossible to construct at the moment due to economic, political, or static reasons are tested in science fiction films. These films are not mere products of imagination but inspiring prototypes of how future cities might take shape. In contemporary architectural practice, it is possible to see that project presentations are prepared with storyboard logic, structures are presented within a dramatic flow of light and story, and architectural representation transforms from a technical drawing into an atmospheric narrative.

A PROPOSAL FOR LAYERED READING: UMBRELLA CONCEPTS AND FLUID IDENTITIES

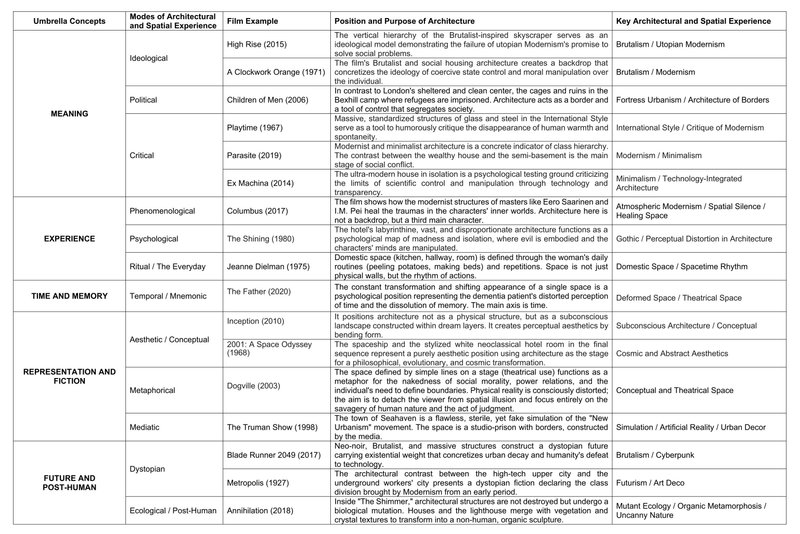

This study is not based on the assumption that architecture in cinema carries a singular and fixed meaning; on the contrary, it relies on the idea that space possesses a multi-layered structure that constantly transforms according to context, narrative, and perspective. To analyze this multidimensional relationship between architecture and cinema, a reading matrix has been created through umbrella concepts such as Meaning, Experience, Time and Memory, Representation and Fiction, and Future and Human.

The categories here are treated not as classes drawing definitive boundaries, but as "analytical lenses" that aid in reading space. Certainly, a cinematographic work is too fluid to be confined to a single category. The same film can be open to ideological, political, phenomenological, or aesthetic readings simultaneously. However, within the scope of this study, architectural and spatial identities considered "dominant" for the films have been highlighted, and a distinct architectural role has been examined under each heading.

In this context, when the matrix is examined; Children of Men, discussed under the heading of "Meaning", positions architecture not as an aesthetic structure but as a political border tool that separates society into "inside and outside," concretizing exclusion. Conversely, Columbus, in the "Experience" category, focuses on the healing, phenomenological, and atmospheric relationship structures establish with the characters' inner worlds rather than their political functions. Under the heading "Time and Memory", where the physical fixity of space is lost, the example of The Father stands out; here, architecture transforms into an unreliable memory space that changes constantly in parallel with mental collapse.

In the plane of "Representation and Fiction", where the form of constructing reality is questioned, The Truman Show presents architecture not as a lived environment, but as a flawless yet fake "simulation decor" produced by the media. Finally, in "Future and Human" fictions, the role of architecture evolves into a post-human discussion. In Annihilation, architecture strips away the human-centric gaze, merging with nature to become an ecological structure that dissolves and undergoes metamorphosis (mutant). Consequently, this matrix demonstrates that space in cinema is not a one-dimensional background, but an active subject that constantly changes—from an ideological wall to a mental labyrinth, from a fake decor to a living organism.

BLURRING THE BOUNDARY BETWEEN REAL AND REEL

At the point we have reached, the line between fictional reality (reel) and physical reality (real) is becoming increasingly blurred. Thanks to technologies like game engines, Virtual Reality (VR), and Augmented Reality (AR), architects can now design gravity-free, immaterial spaces that transcend physical boundaries. This situation radically transforms the role of the architect as well; the architect is no longer just a designer stacking brick upon brick, but a director choreographing experience, atmosphere, and story.

Whether we write a biography for ourselves in 2055 or seek solutions for today's housing crisis, the layers of time, movement, and story that cinema adds to space will continue to be the strongest reference for architecture to produce environments that are not just functional shelters, but possess emotional and phenomenological depth. Architecture and cinema will persist as two ancient narrators feeding each other in humanity's quest for "place-making".